Was Max Reinhardt an influence on Lubitsh? Lotte Eisner thought so. In the The Haunted Screen she tells us that Lubitsch was ‘less sensitive to his influence than other German filmmakers’ (p.79) but also notes the Reinhardt influence in ‘the famous square market place around which Lubitsch was so fond of moving his crowds in Madame Dubarry, Sumurum and Anna Boleyn. In each of these instances, the imitation of Reinhardt effects is of an almost documentary fidelity’ (p. 76).

It is hard for us now to imagine the significance of Max Reinhardt: he was simply the most celebrated man of the theatre of his day, not only in Germany but internationally. Eisner writes that, ‘we should remember that Max Reindhart from 1907 to 1919 (when the revolution brought Piscator and his Constructivist theatre to the fore), was a sort of ‘Kaiser’ of the Berlin theatre. He had become so important that in solid middle-class families everybody skipped the newspaper headlines to read Alfred Kerr’s article on the previous night’s performance. Berliners often went to the Reindhardt theatre several times a week, for the programme changed daily’ (p.47).

Morover, ‘the links between Max Reindhardt’s theatre and the German cinema were obvioius as early as 1913, when all the main actors — Wegener, Bassermann, Moissi, Theodor Loos, Winterstein, Veidt, Kraus, Jannings, to mention but a few — came from Reindhardt’s troupe (Eisner, p. 44). Though the second part of the title of Eisner’s book is often elided, it might be worth reminding ourselves of it here: The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in German Cinema and The Influence of Max Reinhardt. Lubitsch was not an expressionist or at least not much of one (The Doll and other films do show traces). Indeed Tom Tykwer views his later move to Hollywood as a lucky escape from Expresssionism. But Lubitsch did not avoid the influence of Reindhardt nor indeed did he want to. He had a lot to learn; and he learned quickly.

Reinhardt was born Max Goldmann on the 9th of September 1873, in Baden, near Vienna. He was the first of a family of six children. An actor since 1890, he directed his first production in 1900, Ibsen’s Love’s Comedy. He becomes director of the Deutsches Theatre and opened his school of acting there in 1905. In 1906 he bought the Deutsches Theater and opened the Kammerspiele next door. The first production there was Ibsen’s Ghosts.

According to J.L. Styan, from 1910-1912, Reinhardt became ‘known throughout Europe. It was Reindhardt’s privilege to put into practice some of the thinking of the “aesthetic drama’” movement which wanted to combine the art of space and light, of music, design and the spoken word, and of acting, mime and dance. His invention of the Regiebuch (on which more later) as a master promptbook was both a monument to his work – and a necessity if that work was to be carried out’. [i]From 1915-1918 he also becomes director of the Volksbühne in the Bülowplatz, Berlin, saving it from possible extinction during the war years. His first production there is Schiller’s The Robbers. Lubitsch became a Reinhardt actor in 1911, at the height of the director’s fame.

Alfred G. Brooks tell us that Reinhardt’s ‘creative career had spanned the birth and demise, the rejection and acceptance, of the host of forms and movements which sought to provide new perspectives in the visual and performing arts during the first half of the Twentieth Century. Reindhardt influenced playwrights, critics, painters, designers, architects, composers, dancers, actors, directors, and managers. His basically eclectic nature led him to develop an enormous stylistic range which ranged from the studio to the circus, to palaces, vast outdoor arenas, garden theatres, opera houses, small baroque theatres, and cathedral square; all the world was for him a receptive home for theatre. During his lifetime, the vast range of his activities and his widespread influence made him a natural focal point for both admiration and vituperation. Critics and historians who sought neat descriptive labels either described him as a creator of spectacles or attacked him for lack of a clearly identifiable style’[ii].

Rudolf Kommer thought Reinhardt a magician of the stage: ‘To be called a magician and to be one are two very different things. If anyone in the realm of the stage deserves this title, however, it is Max Reindhardt of Baden, Vienna, Salzburg, Belin and the world at large’.[iii]Diana Cooper, daughter of the Duke of Rutland, a great beauty and a cornerstone in British cultural life from WW1 right to the 60s, performed in his production of The Miracle in England and the US and her biographer Phillip Ziegler tells us, ‘Diana knew little about Reinhardt, except that he was popularly reputed to be a genius and probably slightly mad… (he lived) in Salzburg (in the) baroque palace of Leopoldskron’.[iv] However, when The Miracle opened in New York , George Jean Nathan, arguably the most influential critic of the day, wrote in The American Mercury, ‘The theatre we have known becomes Lilliputian before such a phenomenon. The church itself becomes puny. No sermon has been sounded from any pulpit one-thousandth so eloquent as that which comes to life in this playhouse transformed into a vast cathedral, under the necromancy that is Reinhardt. For here are hope and pity, charity and compassion, humanity and radiance wrought into an immensely dramatic fibre hung dazzlingly for even a child to see. It is all as simple as the complex fashioned by genius is ever simple’.[v] A mad genius, living in a palace who directed epic theatre on a mass scale in huge theatres and with whom none could compare. That’s who Lubitsch got a contract with in 1911, when he was nineteen, to play small roles.

Lubitsch had always wanted to be an actor, he loved acting and as is everywhere evident in his films – see To Be Or Not to Be – he loved actors. But Lubitsch was not, as they used to say, exactly an oil painting, and his father tried to discourage him by grabbing his face and pointing it towards a mirror hoping that would bring him to his senses. His mother, who by all accounts ran the family business and the family, supported and encouraged her youngest child. With her help and that of Victor Arnold — a soulful comedian who worked for Reinhardt, gave Lubitsch free lessons and helped get him an audition — Lubitsch finally became a Reinhardt actor in 1911.

Lubitsch was contracted to play small roles only. Bigger parts were given to stars such as Paul Wegener whom Lubitsch later gave leading roles to in his film. But his parents were delighted because, such was Reinhardt’s reputation, that a contract with Reinhardt, even in small roles, was a signal sign of success. In fact it was an honour so great that that many like Dietrich were late to claim it falsely. Reinhardt is a figure most great émigré directors to Hollywood from the German-speaking world (Preminger, Sirk, Siodmak) had some kind of connection to. With Reindhart, Lubitsch played a variety of roles, Launcelot in The Merchant of Venice, the Innkeeper in The Lower Depths. He appeared in the legendary staging of The Robbers and in some of the iconic theatres of his day, The Deutsche Theatre, the Kommerspiele, and later when Reindhart took it over in 1915, the Volksbühne Theatre, barely 200 metres from where he lived.

Lubitsch was lucky to work with Reinhardt for many reasons but foremost is that Reinhardt, who had started as an actor himself and who, according to Otto Preminger, ‘knew more about actors and about the nature of acting talent, than anybody in the history of the theatre’[vi], also revered actors. In ‘Of Actors’, Reinhardt writes, ‘‘It is to the actor and to no one else that the theatre belongs. When I say this, I do not mean, of course, the professional alone. I mean, first and foremost, the actor as poet. All the great dramatists have been and are to-day born actors, whether or not they have formally adopted this calling, and whatever success they may have had in it. I mean likewise the actor as director, stage-manager, musician, scene-designer, painter, and, certainly not least of all, the actor as spectator. For the contribution of the spectators is almost as important as that o the cast. The audience must take its part in the play if we are ever to see arise a true art of the theatre – the oldest, most powerful, and most immediate of the arts, combining the many in one’[vii] An interesting way of looking at actors but one which would be influential to Lubitsch, particularly in the perception that the audience too was an actor and played a role in the drama.

Reinhardt was interested in all forms of popular entertainment, not only theatre but vaudeville, musical comedy, mime, and film. Every Reinhardt actor was potentially a film actor and according to Tom Tykwer, the theatre experience with Reindhardt proved a decisive one in shaping Lubitsch. One must not underestimate the extent of this for Lubitsch has historically been credited with developing not only the concepts of kammertheatre and Massentheater but, importantly in relation to Lubitsch, the concept of ‘Regietheatre’ which gave a centrality to the director. Reinhardt was famous for directing spectacles and crowds, skills that would prove handy for Lubitsch’s historical dramas, he revered actors like Lubitsch did but often gave them precise line readings like Lubitsch was to do, but perhaps most importantly is Reindhardt’s precise attention to all elements of mise-en-scène.

As noted earlier, Reindardt kept a Regiebuch. According to J.L.Styan, the Regiebuch, was ‘a copy of the play interleaved with blank pages. It was a workshop in itself. Prepared in extraordinary detail, and corrected and modified over and over again, it became the indispensable blue print from which many assistants could conduct rehearsals while the master watched over the results. In it he would write down every movement and gesture, every expression and every tone of voice. Diagrams of the stage plan and even three-dimensional sketches of the scene and of its characters would be squeezed into available spaces. Over the years a production lasted, he never finished adding notes in this book, often with pencils and links of different colours’[viii].

Lubitsch started making films in 1913. He never once performed in a starring role on stage for Reinhardt but continued working for the Reinhardt ensemble in small parts until May 1918. Could there be better training for a director in the making than to be working for ‘the first theatre man in the world’ who worked in a way so interestingly transferable to cinema? ix

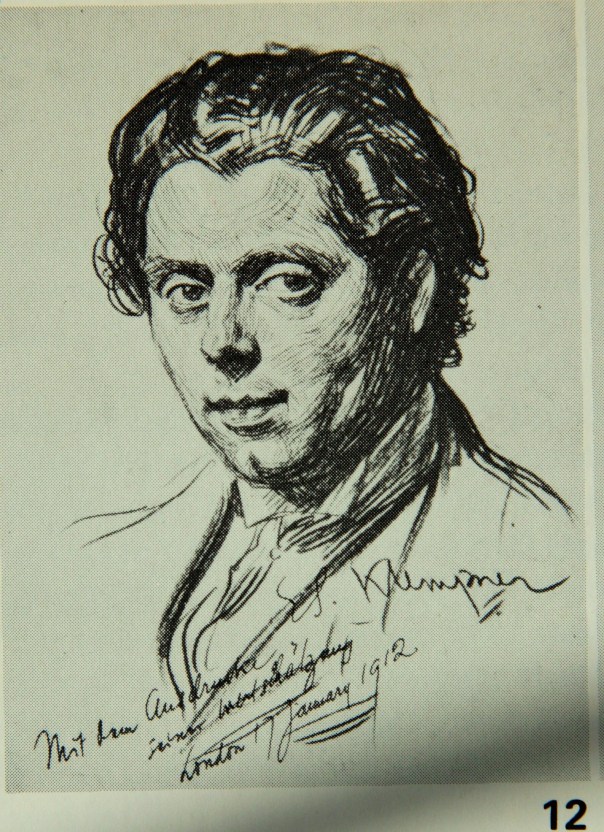

Billy Wilder, who famously asked, ‘How Would Lubitsch Do It’ has a wonderful picture of the Reindhardt troupe, including Louise Rainer, in the collection of his journalism that has recently been published:

José Arroyo

[i] J.L. Styan, Max Reinhardt, Directors in Perspective Series, Cambridge: Cambridge University press, 1982, p. xv

[ii]Alfred G. Brooks, ‘Foreword’, Max Reindhardt 1873-1973: A Centennial Fetschrift, Edited by George E. Wellwarth and Alfred G. Brooks, Archive/Binghampton, New York, 1973, p. i.

[iii] Rudolf Kommer, ‘The Magician of Leopoldskron’ in Max Reindhardt and His Theatre’ ed. by Oliver M. Sayler, trans from the German by Mariele S. Dudernatsch and others, New York/London: Benjamin Blom, 1968. First published in 1924. P.1

[iv] Philip Ziegler, Diana Cooper: The Extraordinary Life of the Raffish Legend who Charmed and Inspired a Society Through Two World Wars London: Hamish Hamilton, 1981, pp. 128-130.

[v] Cited in Max Reindhardt and His Theatre’, op cit., p. ix.

[vi] Otto Preminer, ‘Otto Preminger: An Interview’ Max Reindhardt 1873-1973: A Centennial Fetschrift, op cit, p.11

[vii] Max Reindhar, ‘Of Actors’ in Max Reindhardt 1873-1973: A Centennial Fetschrift, op cit., p.1.

[viii] J.L. Styan, Max Reinhardt, op. cit., p. 120.

[ix] Sylvia Jukes Morris, Rage for Fame: The Ascent of Clare Booth Luce New York: Random House, 1997 p. 110

Additional Bibliography

Lotte Eisner, The Haunted Screen, Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Marx Reinhardt, London: Thames and Hudson, 1965.