A justly famous noir with an ingenious opening sequence tied together by a first person voice-over narration from Ray Milland as magazine editor George Stroud that sets up a theme, a structure for the narrative, the look and feel of a particular world, an objective and a deadline in which to achieve it, as well as thematic tropes (see below).

It stars Ray Milland, Rita Johnson and Maureen O’Sullivan (then married to director John Farrow, and mother of Mia). But it is the supporting cast, George Macready, Elsa Lanchester, Henry Morgan, and particularly Charles Laughton (see below), who delight.

A you can see above Charles Laughton creates a whole series of effects and personality traits through a series of fascinating choices: the way he looks at his watch but then looks in the other direction, the drawling voice, the pinky clearing up the corner of his mouth. He makes the banal fascinating and revealing.

I love this very intense little scene, shot from below, Laughton’s masses of flesh roiling from the massage a very young Hernry Morgan as Bill Womack is giving him as Earl Janoth (Charles Laughton) instructs him to kill. Is Womack more than his henchmen? They never look at each other and we know that Janoth is involved with a woman. Yet the way Farrow sets up these images of evil have an undoubtedly pervy sexual component, one maybe made more potent by not being quite clear.

The film includes a very fine montage which poetically indicates a drunken evening, references the magazine, the job, and the deadline; the wife leaving without him and those pressures; the significance of the painting he outbid the painter to purchase (we don’t yet know that he’s an admirer and collector). There’s something interesting to be explored in how modern art signifies in film noir. In Phantom Lady it’s an indicator of perversion and evil. Here, particularly through Elsa Lanchester’s eccentric and witty performance, it’s treated as a joke. Lanchester’s performance is a delight but the way the film conceptualises the character she plays — Louise Patterson — is unworthy of the film, a cheap stunt amidst work that is otherwise very fine.

The film is of course told in the classic style and has wonderful ‘teachable’ moments like the use of anticipatory space above.

The set-piece at the end is visually dazzling, tense, thrilling, structurally coherent, picking up from the initial voice-over and responding to it. Much of eighties cinema starts from, is organised around, this type of set-piece as spectacular attractions, often forgetting the narrative weight that is built into forties’ versions such as this one. Kevin Costner starred in a loose remake this film, No Way Out (Roger Donaldson, 1985)

Eileen McGarry in her entry on the film in The Film Noir Encyclopaedia writes that the only visual device of note is the ‘slightly–too-wide-angle’ lens, which is used for close-up of Laughton during his vilest moments’. I hope I have shown above that is clearly not the only visual device of note. But it is a most interesting one: ‘his face is (rendered) just ugly enough to break startlingly with naturalism. The use of this subtle distorition increases quite gradually during the film, until, when the flashback catches up with the opening of the film, the viewer may be convinced of the arch villain’s both superhuman and subhuman capabilities. (p. 39).

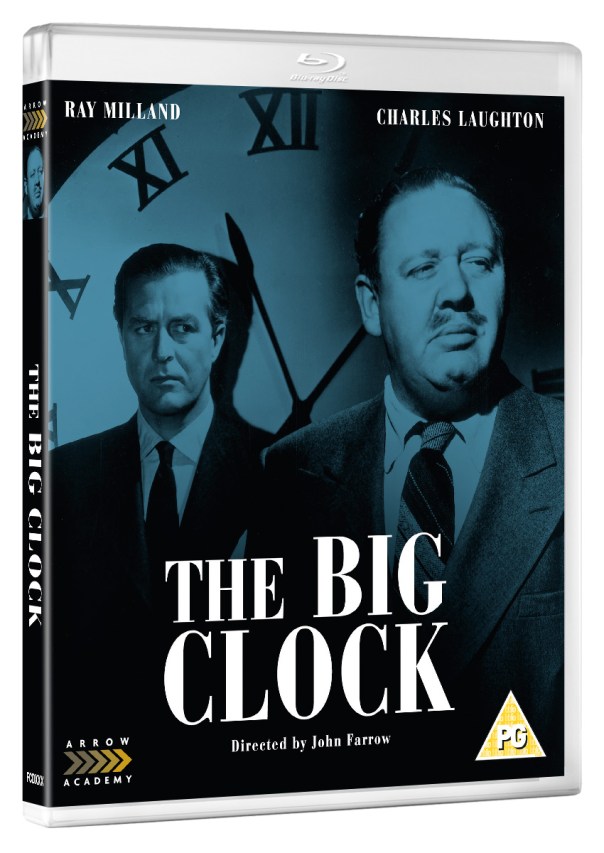

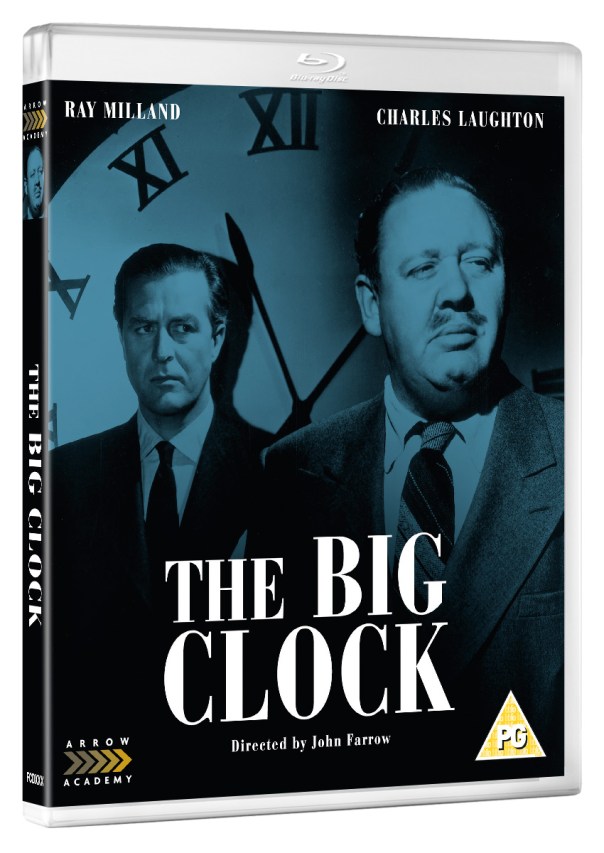

The superb Arrow Academy edition contains a very informative discussion of the film by Adrian Wooton and a film commentary by Adrian Martin. If you can get past how actory Simon Callow is in his every intonation, he gives a superb demonstration in how Charles Laughton is in top form in what is a fallow period of his career and in what basically amounts to a supporting role.

José Arroyo

Like this:

Like Loading...