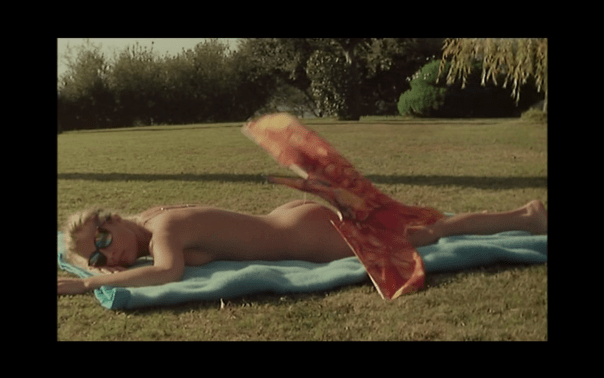

Les innocents aux mains sales/ Dirty Hands is an ingenious thriller by Claude Chabrol with a glorious opening: Romy Schneider plays Julie Womser, a St. Tropez housewife saddled with a rich but impotent husband (Rod Steiger as Louis Womser). As the film begins, she’s sunbathing nude, a kite falls on her bum, a cute man (Paolo Giusti playing Jeff Marle) chases after his kite, she asks him to remove it and offers herself to him. She brings him home; the husband’s there, drunk; they make out anyway; and in what seems a nanosecond, they’re planning his murder. I won’t go into the plot because it’s full of clever twists and continues to surprise until the end. Suffice it to say that it’s an elegant, almost minimalist chamber piece, with outstanding use of sound and the zoom lens so typical of that period.

What I want to focus on here are the clothes. The 70s are often seen as something of a sartorial joke; and that may be true of men’s fashion, particularly when we look at old family photographs of ourselves wearing psychedelic prints, long pointy collars, flares and platform shoes. But it’s a glorious period for women’s fashion, so influenced by vintage forties clothing with it’s variant on the platform, the knee-length suit, the cinched-waisted gowns etc. And as the 2015 exhibit, Yves Saint Laurent + Halston: Fashioning the 70s, at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York in 2015 demonstrated, ‘No two designers defined and dominated the decade more than Yves Saint Laurent and Halston. They were the era’s most influential and celebrated clothing creators, becoming celebrities in their own right. Both have been the subject of countless books, articles, films, and exhibitions.’

I have already in this blog commented on St. Laurent’s clothes for Romy Schneider in Max et les ferrailleurs and César et Rosalie. I here simply want to explore the various looks developed by Romy Schneider, Chabrol and St. Laurent in Les innocents aux mains sales and how they function as aspects of the mise-en-scène to evoke something about the type of woman Romy Schneider’s Julie Womser is, how she’s feeling, how she’s hiding what she’s feeling; how they express what’s happening to her; how the clothes serve the storytelling, characterisation and mood in the film.

Look 1:

After her nude introduction, we’re shown Romy Schneider in a sexy, hip-hugging black dress; elegant, with a jewelled strap but also showing lots of flesh. What’s evoked is wealth, elegance a sexyness that remains distanced , sober and sheathed, but that nevertheless is offered up to Jeff Marle on a white shag rug as soon as her husband has drunk himself into a stupor

Look 2: The kaftan, such a staple of 70s clothing, particularly St. Laurent’s, here conveying elegant couture casual; perfect for St. Tropez and the opposite of what we associate with Demis Roussos. It’s the setting where the husband surprises her with the gift of the car that is to play such an important part in the plot subsequently.

Look 3: The murder

How does a murderess look? Well, a chignon helps. Here Julie/Romy is dressed in black, the collar a hint of the sexuality that drives the passion and edges it into murder. Note too the cut of the dress, the bit of leg and the heels, which seem as much of a weapon as the chignon.

Look 4: The Sleepless Night. Light blue on a darker shade of blue for ‘une nuit blanche’ when she thinks she’s murdered her husband, can’t sleep and gets ready to make up her lies, dress them into view, and lie convincingly to the police.

Look 5: A Kaftan for The Morning After a Murder. This evokes and might be a precursor to St. Laurent’s famous Russian and Chinese inspired collections of the late 1970s. See also look 7.

Look 6 and 7 : Changes to Call the Police, in a darker shade of blue, closer to her sheets than her nightgown in Look 4, but then returns to Kaftan though this one is slightly different than the one above whilst clearly aiming to recall it. Romy’s Julie clearly’s got a collection in her closet

Look 8 and 9:

She returns to look 2, where her husband had bought her the car, but this time to receive a letter from her lover; and then goes to meet with her bank manager and the police at the bank but in the same dress she called the police in earlier but now wearing a black widow’s cape. The looks are clearly associative, symbolic, meant to unconsciously render situation and character whilst also recalling situations and events (here she’s wearing the kaftan she wore when she received the car that was her husband’s token of love but which we’re here told is how her lover drove away the husband’s body. Love turned to murder via money and passion)

Looks 10 and 11, Turbaned in black and wearing a respectable and elegant grey tweed to meet her husband’s friend and business manager, where she once more meets with the police who are getting suspicious of her. When she goes to see the judge she wears the same sober and elegant colour scheme but in a different outfit (see image three, below right). It’s like at this point in the plot the looks, colours, even textures of the character are seeping into one another.

I also want to bring in here some of the associations turban sand berets have for us: Frenchness, as we can see below with Michèle Morgan; a Parisian variant of it we associate with the ‘we’ll always have Paris’ flashback in Casablanca with Bergman and Bogart; the intelligence and coolness we associate with De Beauvoir (here with Nelson Algren; the turban was a signature look for her as it avoided having to do her hair, clearly not a problem for Julie/Romy); and lastly the underworld of noir femme fatales evoked by Bergman’s take on Dietrich in Arch of Triumph (Lewis Mileston, USA, 1948)

Look 12: At her nadir, when all the evidence points against her plotting with her lover to kill her husband; Chabrol and cinematographer Jean Rabier film her in silhouette in a flowing dress, with a flowing scarf; when she comes in we see her all in black, like the unfortunate black widow she believes herself to be. Then, when her husband tells her what happened we flash back to her making love to her lover, the glittering strap being all that’s needed to associate this scene with the beginning (Look 1) where she had sex with her lover and which we now know her husband watched. Now she offers herself to her husband in an echo of the first time she offered herself to her lover, naked and in the sunshine; here enclosed in darkness and distance. At the end, he pays her, like the whore he believes her to be.

Look 13: After her husband returns and pays her to have sex with him, Julie makes herself up to be her version of an elegant whore, with St. Laurent seeming to draw inspiration from Lauren Bacall’s look at the end of To Have and Have Not (Howard Hawks, USA, 1944) and Dietrich in Blonde Venus (Josef Von Sternberg, USA, 1932). The Dietrich reference also recalls how in her biography of her mother, Marlene Dietrich by her Daughter, Maria Riva recounts how hard Dietrich worked at her looks, that she designed them in consultation with Von Sternberg and Travis Banton, and how her performances were powerfully based on the progression of ‘looks’ that had a narrative and dramatic function in the film, particularly as ‘put on the scene’ by Von Sternberg as part of his mise-en-scène

Look 14: In black now, still trying to pretend she’s the innocent and respectable widow but the mise-en-scène showing us the situation is not as as clear as it seems. The grey tweed jacket she wore when she went to see her lawyers is hanging nonchalantly from the chair she’s sitting in and later revealed to be accompanied by a matching skirt:

Look15: In most of the last half-hour of the film Romy’s half black/half tweed turns into full black, eventually accompanied by a crochéd shawl of the sort you’d expect rural peasant widows to wear (and echoing the cape she wore in Look 9 when she first went to meet the authorities). It’ s in this dress that the plot and the actress goes through a whole series of events: she’s discovered not to be a widow, the lover she though dead returns, she gets raped in that dress, and she discovers that when she was thought to be guilty there was no sentence whereas when she’s known to be innocent there is. She does a lot of running — seeking help, fleeing danger — in this dress; and the hem seems to be weighted so that it moves beautifully, in sync and as a result of Julie’s turmoil and distress. It’s the ‘little black dress’ in motion and in performance as put into the scene by Romy Schneider and Yves St. Laurent

Look 15:

Still in black, after she’s been rescued from a rape, and comforted by a red and black tartan blanket, of the sort one associates with Canadian lumber jackets, kilts, homey blankets, and worn like a shawl.

Look 16:

Telling her lawyer (the wonderfully cynical and funny Jean Rochefort), ‘when I tried killing my husband, nothing happened to me, now I try to save him and I’m been punished’. Her look is entirely calm, sophisticated (the hairstyle), demure (the heavy scarf/collar) and as we can tell not only from the cut and fabric of the clothing but from those earrings, rich. However, the chignon seems to bear witness to murder.

Look 17: Suffering chic-ly in minimalist modern interiors that evoke wealth, richness (the gold cigarette lighter on the otherwise empty table), anomie and lonelyness and before the great finale where the darkness calls out her name.

Undressing and Dressing:

In a way the whole film is about dressing and undressing Romy Schneider. She’s a mystery the film 9and the audience) is meant to uncover. We first see her in shades, a reflection of the audience’s desires, a morsel eager to be eaten. The film, then often films her in shadow, partially, in silhouette (see image two below)

The film undresses Julie/Romie only to dress her up in various guises, so she performs different types of femininity for her husband, her lover, the police, the judge, and the audience. She’s often shown having agency over this costuming/construction, the clothes part of her masquerade, the body a kind of currency with which she pays and rewards, both part of the way she performs the various aspects of Julie’s character into being. The most telling point is when her husband returns, pays her to have sex like the whore he thinks she is, and she curls her hair and dresses in white in that Bacall/Dietrich echo is that is the only moment we see her in white in the entire film.

In between displaying her body, selling it or having it raped, the film dresses her mostly in black, with various types of accents; shiny for the lover, sober and sleeklined for the murder, enclosing blue when she talks to the police, or framed by grey tweed at the solicitors, or accented by different shawls. The only moments of colour and brightness are the kaftany casualness with the husband or the moment where she contrasts in binary whiteness to accept that she’s prostituted herself to her husband and is wiling to accept the bargain. It’s really quite extraordinary what a look at the uses of clothing in a film can reveal about character, story and storytelling, not to speak of the performer’s art (which I have not quite done so here though Romy Schneider is glorious). It’s a gorgeous wardrobe by Yves St. Laurent, expressively worn by Schneider and beautifully deployed by Chabrol.

José Arroyo