327 Cuadernos is a beautiful and complex work on biography and on the intersection of memory and history, both individual, as a reconstitution of fragments of the self; and collective, as a shared social history; one that simultaneously examines the intersection of expression and re-presentation whilst keeping in play the various ways in which they differ: very moving.

Andrés di Tella, one of Latin America’s foremost documentary essayist, arrives in Princeton to find writer Ricardo Piglia, a colleague at the University and someone he’s interviewed before many years ago, packing up to return to Buenos Aires after having worked in the U.S. for many years. Piglia’s kept a diary since the age of 16, when politics –the aftermath of the coup against Perón in ‘55 – meant his father, a lifelong Perón supporter, moved the whole family from Adrogué, a suburb of Buenos Aires, to the relative safety of Mar de Plata. His father defended Perón in ’55 and was in prison for a year as a result. “It’s really tough when you’re a kid and your old man is taken away by the cops. That’s really ugly: a strange feeling. But anyway, that’s how it was”.

Andrés di Tella, one of Latin America’s foremost documentary essayist, arrives in Princeton to find writer Ricardo Piglia, a colleague at the University and someone he’s interviewed before many years ago, packing up to return to Buenos Aires after having worked in the U.S. for many years. Piglia’s kept a diary since the age of 16, when politics –the aftermath of the coup against Perón in ‘55 – meant his father, a lifelong Perón supporter, moved the whole family from Adrogué, a suburb of Buenos Aires, to the relative safety of Mar de Plata. His father defended Perón in ’55 and was in prison for a year as a result. “It’s really tough when you’re a kid and your old man is taken away by the cops. That’s really ugly: a strange feeling. But anyway, that’s how it was”.

‘’’55 was the year of sorrow; ’56 was prison and ’57 was even worse” says Piglia, “the trip (to Mar de Plata) was like an exile. Since then, where I live has never really mattered.” In the film, the old writer’s return to Buenos Aires is rhymed, accompanied, contradicted, by that first exile that would turn the displaced and disturbed teenager into the writer of these 327 notebooks; though, interestingly, the images that accompany the latter will be reconstructed, re-imagined and even re-imaged ones. Thus, like we see in the rest of the film, the self, the past, history and society are all both documented and, via acts of interpretation, also to a degree imagined; they offer no immediate or clear access; they’re always mediated, often by more than one element or source.

‘’’55 was the year of sorrow; ’56 was prison and ’57 was even worse” says Piglia, “the trip (to Mar de Plata) was like an exile. Since then, where I live has never really mattered.” In the film, the old writer’s return to Buenos Aires is rhymed, accompanied, contradicted, by that first exile that would turn the displaced and disturbed teenager into the writer of these 327 notebooks; though, interestingly, the images that accompany the latter will be reconstructed, re-imagined and even re-imaged ones. Thus, like we see in the rest of the film, the self, the past, history and society are all both documented and, via acts of interpretation, also to a degree imagined; they offer no immediate or clear access; they’re always mediated, often by more than one element or source.

“There’s nothing more ridiculous that the aspiration of recording one’s own life,” says Piglia, “It automatically turns you into a clown.” But something propelled him into keeping a diary, one that would eventually sprawl across the eponymous 327 notebooks, and he believes the displacement and the diary that ensued as a result was transformative and might have been what turned him into a writer. The film begins with the exposition of a point of origin – that ‘exile’ to the provinces of the film’s protagonist — in which the subject at the film’s present – the return to Buenos Aires from another type of exile in America –- may be found, whilst at the same time acknowledging the narrational and fictional dimensions of such a search. “The art of narration is the relationship the narrator has with the story’s narratives’, says Piglia, ‘that’s what defines the tone”.

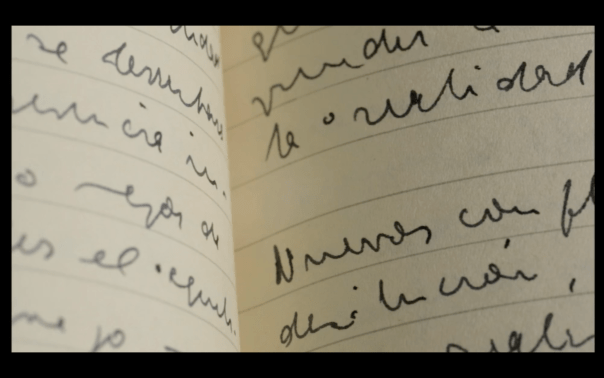

Initially, Di Tella announces the film’s project as ‘‘To keep a diary of the reading of a diary”. But who and what does a diary document? The problems begin at the beginning: “I have the impression I’ve led two lives. The one written in the notebooks and the one fixed in my memories. Sometimes when I re-read it, it’s hard to recognise what I’ve lived. There are episodes set down there that I’d completely forgotten. They exist in the diary but not in my memory. Yet at the same time, certain events that endure in my memory with the vividness of a photograph are absent as if I’d never experienced them.”

Thus begins a complex and sustained exploration of memory and history, how the self is narrated to oneself but also to others, socially. Di Tella consciously delineates a series of methodological problems: How does one film the diary of a writer? What’s a film’s present tense? Who is the narrator and who and what is being narrated? What is the connection between documentary and fiction.

“I can’t even make out my own writing,” says Piglia, “The diary allows you to integrate what happens with a certain documentary style … but (uses) the genre and its tricks to make fiction, an imperceptible fiction. There’s a con there: there’s fiction, and then there’s my real life, my experience; and in between there’s an area of experimentation in which I experiment also with possible lives, you know”.

Piglia’s diaries are not just what’s written in them but also the doodles and sketches they contain – Evita, for example, figures — what falls out of them when opened — pictures of Brecht, an airline ticket from a trip to Cuba, newspaper clippings — ‘Demons Reluctant to be Exorcised– etc; and also what they convey: what does a ranking of boxers reveal about Piglia?

“There’s always a propensity to lists,’ he says, “I think one makes lists in order not to think, right? To rid one’s head of ideas.” He sees another list: love, meaning of life, politics, days of soccer, theatre, movies, literature. “It’s another list but more internal, see? The meaning of life! Isn’t that marvellous. And here it is, side by side with boxing!”

Until the filming, Piglia’s never re-read his diaries. He started to type them up at various times but failed to follow through. Now, as he tries going over them once more, problems arise: ‘It’s hard going back over your own life. It’s not easy’. Moreover, he sometimes can’t make out his writing, often doesn’t remember the events described and eventually declares: ‘ ‘I don’t like this. I don’t like anything I’m reading. That could be the title of the film.’

Half-way through the film, Piglia develops a serious illness which the film doesn’t reveal but which we now know to be Lou Gherig’s desease. Thus the film has to change tak. Piglia now needs help writing and an assistant is found for him. The scratching sound of the pen that has accompanied most of the film until now gives way to the tapping on a keyboard and it’s as if the change in sounds leads to a change in tone.

The illness leads to a series of interrogations on the nature of the project and thus of the intersections of biograpy/autobiography/ fiction: Autobiography could be a collage (of other autobiographies); the project could re-focus on what wasn’t written down but is still remembered; memory comes to us as splinters, flashes, full of light, perfect, unconnected; that’s how it should be written, affirms Piglia. He experiments with putting diaries in third person; he talks about himself as if he were someone else. “A writer’s diary is also a laboratory. Not so much experiences but rather experiments”. He re-writes, makes changes. Literature, he says, is the place in which someone else always does the talking. He thinks on the connection between his fiction and his diaries:

The illness leads to a series of interrogations on the nature of the project and thus of the intersections of biograpy/autobiography/ fiction: Autobiography could be a collage (of other autobiographies); the project could re-focus on what wasn’t written down but is still remembered; memory comes to us as splinters, flashes, full of light, perfect, unconnected; that’s how it should be written, affirms Piglia. He experiments with putting diaries in third person; he talks about himself as if he were someone else. “A writer’s diary is also a laboratory. Not so much experiences but rather experiments”. He re-writes, makes changes. Literature, he says, is the place in which someone else always does the talking. He thinks on the connection between his fiction and his diaries:

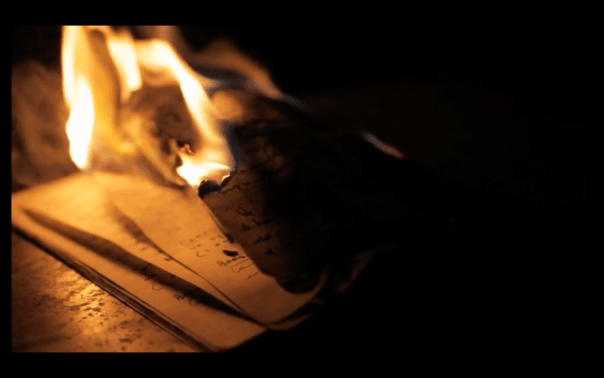

“It’s as if in my novels there’s always this anchor. Hooked to something that actually happened. Sometimes found in diaries.” He fantasises about publishing the diaries under the name of one of his fictional characters, Emilio Renzi (which is how the first volume has since been published). Sometimes, he just dreams of setting match to paper, burning them all and be done with.

“It’s as if in my novels there’s always this anchor. Hooked to something that actually happened. Sometimes found in diaries.” He fantasises about publishing the diaries under the name of one of his fictional characters, Emilio Renzi (which is how the first volume has since been published). Sometimes, he just dreams of setting match to paper, burning them all and be done with.

De Piglia’s illness becomes more serious and Di Tella is unable to film for two months. What to do? Di Tella does as Enrique Amorim did in the 30s and films Piglia’s friends, tries to talk about him through filming them: Roberto Jacoby, Tata Cedrón, Germán Garcia, Gerardo Gandini. Gandini like possibly Horacio Quiroga in Amorim’s filming, dies unexpectedly shortly after these images were filmed. Even as the film tries to bring Piglia to life through various means and in various guises, death haunts this project.

327 Notebooks is a complex and sustained exploration of memory and history. The times when one feels part of a historical event, when a historical event intersects with one’s personal life, changes it and one is tossed about by the waves of change and feels part of history are few. For Piglia, “’55 was a moment were history enters life”, so was the coup of ’66 and the death of Che Guevara: “It rained a lot that day…I have an image of myself crossing the street flooded with rain with the awareness that Che was dead.”

The film uses found footage gathered from a private archive of Super 8 films, as well as the leftovers of 16mm footage shot for news reports (what was broadcast has been lost; but the trims survive). Thus Piglia reading of events he lived but can’t remember is interspersed with historical events (people waving their white handkerchiefs as a symbol that Cristo Vence! (Christ Wins!), Peron’s wife giving an emotional speech from the presidential balcony, the debates around whether the photographs of Che Guevara’s corpse are authentic), some home movies, other people’s memories but with the people now dead or scattered away so that they can’t re-invoke them; someone’s else’s home movies standing in for a social memory, something akin to what one might have experienced.

The film uses found footage gathered from a private archive of Super 8 films, as well as the leftovers of 16mm footage shot for news reports (what was broadcast has been lost; but the trims survive). Thus Piglia reading of events he lived but can’t remember is interspersed with historical events (people waving their white handkerchiefs as a symbol that Cristo Vence! (Christ Wins!), Peron’s wife giving an emotional speech from the presidential balcony, the debates around whether the photographs of Che Guevara’s corpse are authentic), some home movies, other people’s memories but with the people now dead or scattered away so that they can’t re-invoke them; someone’s else’s home movies standing in for a social memory, something akin to what one might have experienced.

As the film unfolds this interlayering of history, the social, the personal, the personal as history, events unremembered, memories unrecorded, all these partial but interacting layerings of aspects, of parts we sometimes reconstitute into a whole and call the self, becomes more deliberately metaphoric, thus we’re asked to interpret the meaning of a polar flight with huskies being pushed onto a plain, or at the end of the film, a horse tamer, bronco-ing through the horse’s every attempt to throw him.

As the film unfolds this interlayering of history, the social, the personal, the personal as history, events unremembered, memories unrecorded, all these partial but interacting layerings of aspects, of parts we sometimes reconstitute into a whole and call the self, becomes more deliberately metaphoric, thus we’re asked to interpret the meaning of a polar flight with huskies being pushed onto a plain, or at the end of the film, a horse tamer, bronco-ing through the horse’s every attempt to throw him.

In voice-over Di Tella recounts how according to Piglia: “in the diaries an unknown man appears, unknown even to him, an intimate character who only exists in the pages of the notebooks; someone darker, more violent, sentimental, vulnerable. It’s not the same man his friends know.” The man that appears to us in the film is probably also different to the man that appears in the diaries, or the person who unfolds and changes through history and who write them in the process of changing who that self, those various selves, was in the very process of transformation, of perhaps altering into someone else. It’s a great film that manages to convey all of this whilst interrogating the various grounds of each step of the representation itself. And the found footage also gives it a touch of the poet, those powerful images that evoke a social history one recognises but can’t quite pin down into a singular meaning. Very beautiful.

In voice-over Di Tella recounts how according to Piglia: “in the diaries an unknown man appears, unknown even to him, an intimate character who only exists in the pages of the notebooks; someone darker, more violent, sentimental, vulnerable. It’s not the same man his friends know.” The man that appears to us in the film is probably also different to the man that appears in the diaries, or the person who unfolds and changes through history and who write them in the process of changing who that self, those various selves, was in the very process of transformation, of perhaps altering into someone else. It’s a great film that manages to convey all of this whilst interrogating the various grounds of each step of the representation itself. And the found footage also gives it a touch of the poet, those powerful images that evoke a social history one recognises but can’t quite pin down into a singular meaning. Very beautiful.

Seen at EICTV in the presence of the director and available to view at as a VOD rental on Vimeo at: https://vimeo.com/ondemand/327cuadernos

.

José Arroyo