In an excellent piece entitled ‘Michael Curtiz’s Doris Day Period’, Gary Giddins writes of director Michael Curtiz, ‘Stylistically, his work is distinguished by aggressive visual compositions (signature shot: two characters shoulder to shoulder, facing forward), forceful acting, quick cuts, fluid camerawork, shadow play, location inserts, romantic and period realism, the kind of speed that results from keeping a story on track and free of distraction, and, above all, a shameless mastery of emotional manipulation (loc 1455)*

It’s that ‘shadow play’ that I want to illustrate here, as Curtiz uses it in a variety of ways, to set mood but also to convey and hide information. It recurs in a variety of genres. It’s always a striking image, sometimes an exciting and evocative one.

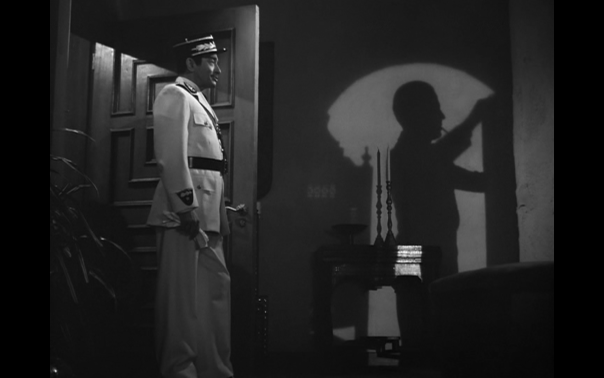

Captain Blood (1935)

In Captain Blood, we get this striking image below. Captain Blood (Errol Flynn) is curing a man but the authorities are already on their way to arrest him for doing so and doing a doctor’s duty in an unjust society will condemn him to a future of slavery and piracy with the possibility of death overhanging the rest of the narrative.

The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936):

Here shadows are used in a whole variety of ways to set mood, create tension, both indicate the trouble of a place, but also people in a place, and the anxiety provoked by certain actions.

Kid Galahad (1937)

Curtiz is sparing with the typical projecting of shadows onto a wall to give us an indication of what’s happening off-screen, to show us without showing us, whilst shading it with hint of evil, until the very end, where Bogart shoots at someone without being seen so as to create a distraction so he can go for his real target, Edward G. Robinson:

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938):

In his brightly lit masterpiece, shadows thrown on a wall contribute to, amongst other things, making the famous sword-fight with Basil Rathbone extra spectacular.

and later on, Claude Rains’ evil Prince John, is associated with the death and defeat of his fallen soldiers whilst the shot pans and we see him counting his money.

Angels With Dirty Faces (1938)

Here James Cagney, going to the chair, and pretending to be scared so that the boys who hero-worship him might not be too tempted to emulate him is, wisely, shown by his shadowed reflection. It’s not easy to believe Cagney being scared of anything. Shadows play is only brought to the last scenes in the film. We see Cagney in jail throwing his cigarette butt to his uniformed jailer (below left) and, before, that, as seen on the right, taking the priest played by Pat O’Brian hostage, in a vain attempt to escape.

And Curtiz doesn’t just deploy this in gangster films, as above, but even in screwballs such as Four’s a Crowd, where the security guard at the mansion is chasing after Errol Flynn before he escapes into Olivia de Havilland’s bedroom.

The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939)

Here Bette Davis as Queen Elizabeth is first shown to us as a shadow. She’s icon and ruler first, that we hear Bette Davis inimitable clipped voice as part of the image renders the fusion of two icons (Bette and Elizabeth, Bette as Elizabeth) even more powerfully.

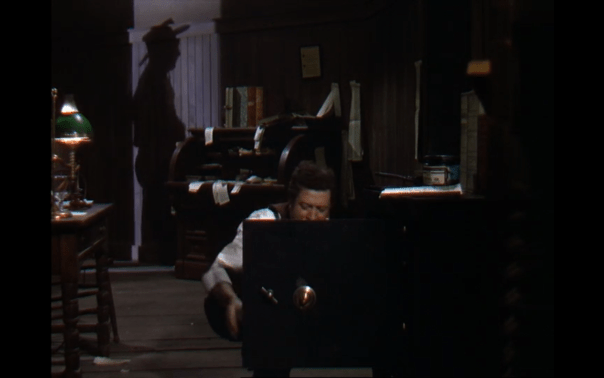

Dodge City (1939):

Here the murder that sets of the last part of the film is shown to us as a shadow so that we see what the journalist doesn’t, and obviously to add to the ominousness and danger of it all.

The Sea Hawk (1940)

Hung from a mast but shown as a shadow on the ships floor. It renders the violence of the act both more palatable and more powerful, the shadow-play narratively warning, but setting a mood for future developments, and generating an image that’s graphically arresting whilst removing that which is graphic or explicit about it.

Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942)

Here shadows are cast on death scenes (below, top left), to convey a particular point of view on narrative information (below, top right) and to show the long shadow cast by a beloved entertainer even in the Oval office.

Casablanca (1942)

In Casablanca, like in Yankee Doodle, a shadow of the name of a place, brings the narrative information indoors (see top) and we also have the use of shadows to bring extra-diagetic space into the frame whilst conveying a mood (see bottom). Arthur Edeson’s lighting is very beautiful and shadows are cast over that whole world and those relationships. The close-ups before Bogart’s flashback to Paris are superb.

Irving Berlin’s This is the Army (1943):

‘Shadow work’ appears even in musicals, to continue the entertainment through different spaces.

Mildred Pierce (1945)

Mildred Pierce is one of the great noirs, with dazzling use of shadows throughout; so, rather than illustrate by using image capture, I thought it best to use excerpt a whole scene. This is from the beginning, where Mildred (Joan Crawford) invites Wally (Jack Carson) up to the beach house so he can take the fall for the murder of Monte (Zachary Scott). This is the moment where he begins to tweaks that she’s left and has only invited him in for reasons other than a potential tryst:

Shadows are cast over identity in Romance on the High Seas, 1948

Shadows demarcate the difference between what should be and what is in My Dream Is Yours, 1949.

Kirk Douglas and his music is a shadow on Lauren Bacall’s happiness in Young Man With A Horn, 1950. If only the light would shine on that sapphic lamp with phallic symbol extending, everyone would be a lot happier.

Poverty and unemployment hover over the family in I’ll See You in My Dreams (1951) as Doris phones for help.

Pain, poverty and his father’s emasculation overhang and literally shadow Elvis’ rise to success in King Creole (1958):

I was going to do this for all of Curtiz’ films in which I saw it appear. But in doing so, it became clear that this type of ‘shadow work’ appears in all his films. I think one can quite here and quite convincingly argue that this is indeed a characteristic of his visual style.

Lastly,, I thought I was making some original major discovery but I see that directors and cinematographers have long been familiar with this aspect of Curtiz’ work as we can see in this excerpt from Gary Leva’s Michael Curtiz, The Greatest Director You’ve Never Heard Of:

José Arroyo

*Gary Giddins, ‘Michael Curtiz’s Doris Day Period’ Warning Shadows: Home Alone With Classic Cinema New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2019, Kindle version.