Last week, whilst visiting Sanctuary Wood, a WW1 museum in Belgium, original trenches still visible outside, the history surrounding them still vividly commemorated and mourned, I came across this image (Fig 1, above). I’s from a big wooden stereoscopic viewer where you place your eyes on peepholes and the mechanism creates the impression of three dimensionality in order to convey the disasters of war. I managed to get my camera’s lens only through one of the peepholes but succeeded in capturing this image, by necessity partial. It reminded me of Goya’s ‘ ‘The Disasters of War’, particularly the ‘This is Worse’ image (see Fig. 2 below).

It also seemed to coalesce and bring into focus a series of art exhibits, experiences and reading of the past few weeks, that all of a sudden seemed to be meaningful not only in themselves but in relation to each other: Firstly, a superbly moving installation by the great Iranian artist Farideh Lashai called ‘When I count there are only you…but when I look there’s only a shadow’, a conversation across the centuries — centuries of war and destruction — with Goya’s ‘‘The Disasters of War’, currently on display at the Prado museum, exhibited amongst its superb collection of Goyas, the best collection in the world. Farideh’s work — on which more later — is in dialogue with Goya’s.

Fig 3

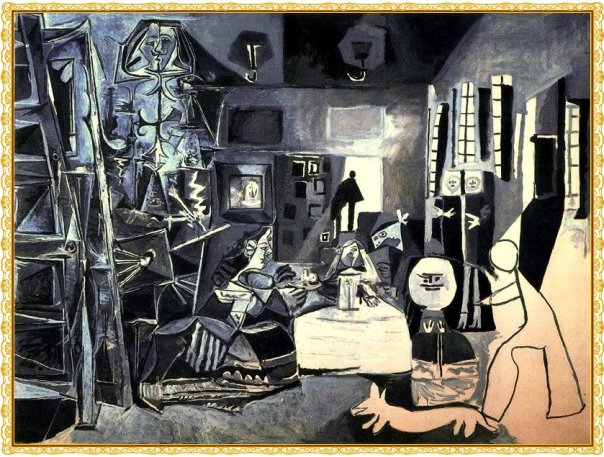

Secondly, I’ve also been thinking about the current ‘Pity and Terror: Picasso’s Path to Guernica’ exhibit at The Queen Sofia Museum in Madrid, which so well demonstrates how Guernica’s depiction of disorientation, suffering and terror quickly became an emblem of the modern condition. The exhibit shows how in Guernica, the world had been “changed into a furnished room, where all of us, gesticulating, wait for death” Picasso’s Guernica is also very much in dialogue with Goya’s work. In the ‘Picasso: Tradition and avant-garde’ exhibit, jointly hosted by the Prado and the Queen Sofia museums in 2006 as part of the celebrations of the 25th anniversary of Guernica’s return to Spain, the Prado demonstrated Picasso’s dialogue with art history, his re-workings and explorations of works like Velazquez’s ‘Las Meninas (see below)’ and works by other key key painters in the the history of art such as Rubens, Raphael, Titian, Rembrandt, and many others, including Goya.

At the Queen Sofia, what was explored more particularly was Guernica and its legacy. I remember being impressed by corridors exhibiting — in chronological order — all the sketches Picasso produced in preparation for it. Picasso worked every-day, prodigiously so, and every-day the figures became clearer, simpler, more powerful. The installation also placed together Goya’s Third of May (1814) with Manet’s The Execution of Maximilian (1869, see Fig 3. above) as well as Picasso’s own The Charnel House (1945) — so clearly a re-working of Goya’s The Third of May — and Massacre in Korea (1951, see below), in relation to Guernica, the earlier ones acting as contexts for it.

The third element, tied to all of the above, that’s been on my mind is T. J. Clark’s superb essay in the August 17th issue of the London Review of Books on Picasso and Tragedy (https://www.lrb.co.uk/v39/n16/tj-clark/picasso-and-tragedy) . In it he writes:

‘For some reason – no doubt for many reasons, some of them accidental or external to the work itself – Picasso’s painting has become an essential, or anyway recurring, point of reference for human beings in fear for their lives. Guernica has become our culture’s Tragic Scene. And for once the phrase ‘our culture’ seems defensible – not just Western shorthand. There are photographs by the hundred of versions of Guernica – placards on sticks, elaborate facsimiles, tapestries, banners, burlesques, strip cartoons, wheat-paste posters, street puppet shows – being carried in anger or agony over the past thirty years in Ramallah, Oaxaca, Calgary, London, Kurdistan, Madrid, Cape Town, Belfast, Calcutta; outside US air bases, in marches against the Iraq invasion, in struggles of all kinds against state repression, as a rallying point for los Indignados, and – still, always, everywhere, indispensably – an answer to the lie of ‘collateral damage’.’Clarke expands on his definition of ‘Tragic Scene’ as follows: ‘the moment in human existence, that is, when death and vulnerability are recognised as such by an individual or a group, but late; and the plunge into undefended mortality that follows excites not just horror in those who look on, but pity and terror (see footnote 1)

In the rest of the article T. J. Clarke sets out definitions of tragedy and their connection to Pity and Terror, the connection between tragedy and the monstrous ( see quotes under footnote 2), the relationship of spectacle to tragedy and the monstrous (see quotes under footnote 3), and how this figures in relation to the representation of space (and connected to the comments on the world as a furnished room above, but also the quotes under footnote 4). Clarke concludes:

‘Perhaps, then – though the thought is a grim one – we turn to Guernica with a kind of nostalgia. Suffering and horror were once this large. They were dreadful, but they had a tragic dimension. The bomb made history. Mola and von Richthofen were monsters in the labyrinth. ‘And everywhere we see them perishing, devouring one another and destroying themselves.’ It may be true, in other words, that we pin our hopes on Guernica. We go on hungering for the epic in it, because we recoil from the alternative – violence as the price paid for a broken sociality, violence as leading nowhere, violence as ‘collateral damage’, violence as spectacle, violence as eternal return. But how could we not recoil? And does not the image Guernica presents remain our last best hope? For ‘vulnerability, affiliation and collective resistance’ still seem, to some of us, realities worth fighting for.

‘The Disasters of War’, part of Goya’s Caprichos (Caprices), is a series of sadnesses and horrors drawn in two sketchbooks in 1797 and 1798 and published in 1799. According to The New York Times: they detailed ‘abuses by the Roman Catholic Church, societal ills from pedophilia to prostitution, and rampant superstition in an age of revolution and terror.’ ‘What is a ‘capricho?‘ asks Robert Hughes in Goya, his masterful work on the painter (Vintage Books, 2004)(https://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/30/nyregion/goyas-etchings-of-a-dark-and-complicated-past.html): ? ‘A whim, a fantasy, a play of the imagination, a passing fancy….the word derives from the unpredictable jumping and hopping of a young goat (p. 179)…Goya, however, was the first artist to use the word ‘capricho’ to denote images that had some critical purpose: a vein, a core, of social commentary. This he made clear with the notes that he wrote on a drawing for what was to be the first of the Caprichos, but whose final etched version got shifted to plate 43: The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (Hughes, p. 180, see image below).

Writing on the ‘Sleep of Reason’ image, Sarah C. Shaefer says (https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/becoming-modern/romanticism/romanticism-in-spain/a/goya-the-sleep-of-reason-produces-monsters), ‘

Some other interpretations of this iconic image of the Enlightenment and its limits by Aldous Huxley and others can be found here (http://www.19thcenturyart-facos.com/artwork/dreamsleep-reason-produces-monsters)

Revolution, chaos, war, disaster, death; all figures so heavily in Goya’s work that there was an exhibit at the Prado, with accompanying catalogue (see image above) just on this subject in 2008. Goya was born in 1746 in Aragon and died in exile in Bordeaux in 1828. He suffered from an illness in 92-93 that left him deaf, made him determined to follow a path of free expression in painting and resulted in work that was darker, anguished troubled, and that manifested itself not only in the etchings but also in the portraiture, most famously in his painting of Charles IV and his family (see below). Has a royal family ever been depicted thus?

These are the years of the French Revolution and subsequent terror from 1789 onwards. The French declaring war with Spain and the invasion of Rosillon by the French in 1793, the defeat of the Spanish Armada by Nelson in Cape Saint Vincent in which Spain lost Trinidad to the English interrupting traffic between Spain and its colonies in the Americas. These are the years of the Bonaparte and the 18th Brummaire (1799). These are also the years Goya becomes the highest ranking Royal Painter, the ‘Primer Pintor de Camera.’ And this is all before The Spanish War of Independence against the French (1808-1814) and the fatal consequences that arose form it from 1814-1820, from the moment that Napoleon is exiled to Elba to the moment Fernando VII swears to the new constitution in the Cortes in Cadiz in 1820.

Goya’s deafness isolated him, made him delve more into his own consciousness and into his own thought. But his vision was clear and what he saw was horror after horror. And he had the daring and the skill with which to express it (random examples that caught my eye from the Goya in Times of War exhibit below). According to Ana Martínez Aguilar, ‘The Disasters of War, for many (Goya’s) best series of etchings, is the work of a mature man, one whose made Enlightenment thought his own, humanising it. He articulates a personal vision of the world, penetrated by skepticism and, at the end, in my view, by compassion understood as empathy to the suffering of others’.1

The great Iranian Artist FarideChoiph Lashai (1944), was greatly inspired by Goya, particularly the etchings, the caprichos that constitute ‘The Disasters of War’. Like Goya, Farideh lived through times of revolution, immense social changes, death and disaster, and the rule of power, fear and terror, in what we now called Iran but was then called Persia. In 1951 Mohammad Mosaddeqh’s nationalisation of the petroleum industry resulted in a military coup which, with the help of the CIA and MI6 removed him from office, put him in jail and facilitated the return to power of the Shah. In 1971 we see the start of armed resistance in Siahkal. In spite of extraordinary repression, what ends up becoming an Iranian revolution deposes the Shah in 1979 only to replace it by the Popular Republic of Islam ruled by the Ayatollah Khomeini, Imperial rule deposed only to be replaced by Theocratic one. This is then followed by the Iraq-Iran war from 1980-1988 where war and religious power downgrades reason, upgrades superstition, stabilises the tyrannical and results in the kinds of effects so well dramatised by Goya in the ‘Sleep of Reason’ and in his ‘Disasters of War’. Lashai was imprisoned from 74-76 and lived through Hussein’s bombardment of Tehran in 1986.

The work of both Goya and Lashai, develops against a backdrop of revolutionary though and in an intellectual context of writers, dramatists, artists and philosophers: the historical context for Goya was the Enlightenment, The French Revolution of 1789 and the Spanish War of Independence; Lashai’s world is that of protest and liberation movements in the ’60s and ’70s, the Islamic Revolution in Iran in 1978-79, and the Iraq-Iran war 1980-1988)

All of this brings me to Farideh Lashai’s multimedia installation, the meeting of Goya and Leshai, and how Leshai re-works Goya, my original reason for writing this post (see clip above). The Installation is situated in the Prado between the room that houses Goya’s The 2nd of May and the The Third of May and the room that houses his Black Paintings. Farideh took only 80 of the 82 etchings that make up The Disasters of War so she could form a rectangle of 8×10. She then did her own etchings based on Goya’s, copying them, but removing all figures from background so that they seem to be only landscapes. These landscapes act as a kind of screen. She then did an animated film that reinserted the people onto the landscape. When the film, constructed as a circle that acts as a both iris and spotlight hits the screen, what we see are the landscapes first empty of the terror it once housed as they might now once again be in real time, now once more populated, but populated by corpses and other disasters of war it once was a sight for. The spotlight is only ever partial, the moving spotlight does not usually fully reveal what is in each individual and rectangular etching. It acts as a kind of memory. It’s fleeting, partial. The music, Chopin’s 21st Nocturne in C minor, adds to the beauty and the sadness.

Watching the installation reminded me of returning to the Montreal neighbourhood I grew up in after an absence of twenty years, something every tango lover knows leads only to sadness and heartache. I recognised every street, every building, every monument. But whereas once I walked those streets surrounded by friends and saying hello to dozens of people as I walked, I now knew no one. The site being the same had the effect of rendering me spectral to myself. I had changed. It hadn’t. My presence there was almost a ghostly one. Except for the people who, because no longer there in situ presented themselves and walked with me in memory. I walked through those real streets but now with the people I once loved, made present in my mind through their absence on the street. Lashai’s work makes one think of such things. I found it interesting that the Spanish title ‘Cuando cuento estás solo tú…pero cuando miro hay solo una sombra’, translates as ‘When I tell there is only you….but when I look there is only a shadow’. But the English Title of the installation is ‘When I Count, There Are Only You…But When I Look, There is Only a Shadow’. I wonder if that an error in translation or does the ‘is’ become ‘are’ as the installation unfolds, pluralised just as I became we walking through those all too familiar streets where I once knew so many but now walked alone?

The catalogue of the installation is prefaced by an excerpt from T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land from the first section, ‘The Burial of the Dead’

What Leshai does with Goya is to make us pay attention to what is already in Goya but which our times might have made us less sensitive to. Her reduction of Goya’s etchings to bare landscapes only underlines, as the spotlight hits them and reveals the drama of the events, the fate of the people — the full horror. They’re settings for the cultural ‘Tragic Scene’ T.J. Clarke attributes to Picasso’s Guernica. We see, for a moment, in a glimpse, the death and vulnerability that once peopled the scene. We see it too late. The tragedy has happened. We see it as a series of spectacles through the etchings. But that ‘undefended mortality’ not only excites horror but evokes pity and terror. Leshai makes whole what time might have erased from ‘The Disasters of War’. She looks under the stony rubbish, into the broken images, extracts the shadow, and does indeed evoke in T. Eliot’s words ‘fear in a handful of dust’. The Chopin adds a serene melancholy to the watching of that which we cannot change. Even if our view now, seen though the centuries and across cultures, can only be a partial illumination. It’s a masterpiece of an installation, a dialogue between works, and by masters of their form.

José Arroyo

Footnotes, all from T.J. Clarke

- ‘Tragedy,’ he says in a famous passage, ‘is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain grandeur; in language embellished with each kind of artistic ornament, the several kinds being found in separate parts of the play … producing pity and terror in the audience, and thereby cleansing the audience of these emotions.’ The word bequeathed to us by the last sentence is katharsis, whose roots seem to lie in medicine or rituals of purgation. Why the experience of pity and terror in the theatre is cathartic Aristotle never explains – he seems to take it as self-evident. Some have questioned Aristotle’s confidence, others (like Brecht) have disapproved of the cleansing. Is pity an emotion we want to be purged of? Are we right to call it an ‘emotion’ in the first place? But let me put these questions aside – they take us towards insoluble mysteries – and return to the question of the monstrous. Aristotle knows full well that horror and disproportion are intrinsic to tragedy’s appeal. But he makes a distinction between the appearance of the dreadful on stage and its unfolding in an action – its progress towards a moment of recognition. Tragedy, he admits, is partly a matter of theatrical effect: the circular stage, the dancing and wailing chorus, the backdrop of the ‘scene’. He calls this physicality ‘spectacle’ and is conscious of its power:

Pity and terror may be aroused by means of spectacle; but they may also result from the inner structure of the piece, which is the better way … For the plot ought to be so constructed that, even without the aid of the eye, he who hears the tale will thrill with horror and melt to pity at what is taking place … To produce this effect by mere spectacle is a less artistic method … Those who employ the means of spectacle end up creating a sense not of the Terrible but only the Monstrous, and are strangers to the true purpose of tragedy.

2. ‘I doubt that an artist of Picasso’s sort ever raises his or her account of humanity to a higher power simply by purging, or repressing, what had been dangerous or horrible in an earlier vision. There must be a way from monstrosity to tragedy. The one must be capable of being folded into the other, lending it aspects of the previous vision’s power.’

‘The terrible and the monstrous – these do seem repeated terms of Picasso’s art after 1925. And spectacle, as Aristotle understood it, is certainly Picasso’s god. But in Guernica didn’t he find a way to make appearance truly terrible, therefore pitiful and unforgivable – a permanent denunciation of any praxis, any set of human reasons, which aims or claims to make what actually happens (in war from the air) make sense?’

3. We are circling back to Aristotle’s notion of ‘spectacle’, which extends to all things appealing primarily to the faculty of vision: the Greek word is opsis. Modernity is a system of incessant opsis. So the prominence of war in modernity – and the fear that it may be modernity’s truth – is not a matter of more and more (or less and less) actual conflict, but of violence as the form – the tempo, the figure, the fascinus – of our culture’s production of appearances.

4.’ spatial uncertainty is one key to the picture’s power. It is Picasso’s way of responding to the new form of war, the new shape of suffering. Uncertainty about the nature of space is, further, a charged matter for him – especially when the space in question is that of a room, a table, walls, windows, a chequerboard floor. For the room is the form of the world for Picasso. His art depends on it. Guernica puts in question, that is, the very structure of Picasso’s apprehension’.

‘It is this combination of domesticity and paranoia – of trust in the room and deep fear of the forces the room may contain – that makes Picasso the artist of Guernica.’

Other Footnotes: 1, Ana Martínez de Aguilar, ‘He custodiado cada cosa dentro de mi’, Farideh Lashai: Cuando cuento estás solo tú…pero cuando miro hay solo una sombra, MadridMuseo Nacional del Prado, 2017. My own translation from ‘Los Desasters de la guerra, para muchos, su mejor serie de estampas, es la obra de un hombre maduro, que ha hecho suyo el pensamiento de la Ilustración humanizándolo. Articula una visión personal del mundo, penetrada por el escepticismo y, al final, a mi juicio, por la compansión, entendida como empatía hacia el dolor ajeno’, p. 33.

1 thought on “Notes on Goya, Picasso, T. J. Clarke on Picasso as a context for Farideh Lashai’s ‘When I count there are only you…but when I look there’s only a shadow’”