Torn Curtain is widely thought to rank amongst the worst of Hitchcock, a failed emulation of the Bond films so popular in the era, and remembered by Hitchcock afficionados mainly for the rupture in the relationship between Hitchcock and composer Bernard Herrman: Herrman wrote a score for the film but Hitchcock didn’t like it and commissioned a new, pop-ier one from John Addison. It was the last time they worked together.

David Thomson in The New Biographical Dictionary of Film writes, ‘No matter how many times the profit ratio of Psycho is repeated, it does not alter the fact that Hitchcock made several flops, several films in which the entire narrative structure — over which he spent such time and care — is grotesquely miscalculated. Stage Fright, The Trouble with Harry, Lifeboat, and Torn Curtain seem to me thumpingly bad films, helpless in the face of intransigent plots, true delicacy of humour and uncooperative players (p.401).’ It’s all relative I suppose but I don’t agree; or rather, Hitchcock’s worst offers more pleasures than almost anybody else’s best. I found a lot to like in Torn Curtain.

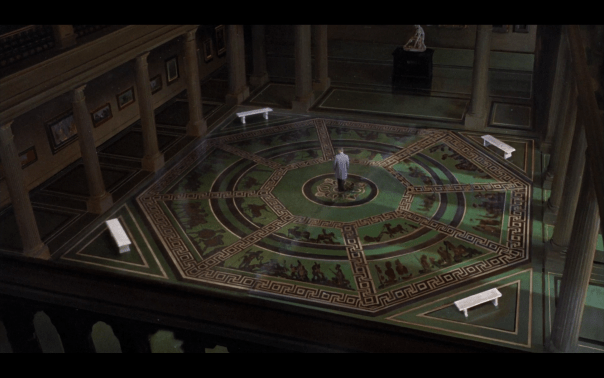

The story is an espionage thriller about a Professor (Paul Newman) and his assistant/fiancée (Julie Andrews), three months from tying the knot, who are at a scientific conference in Scandinavia when, much to the fiancée’s astonishment, the Professor decides to defect to East Berlin. Is he a traitor or is he a spy? We soon find out. The film boasts memorable and typically Hitchcockian set-pieces: the killing in the country-side farm, Paul Newman being followed in a museum, the couple escaping the university, the way they outmanoeuvre the Stasi and manage to escape from the ballet when every entrance is blocked by police, etc. Really, even minor Hitchcock is full of pleasures. Of Hollywood filmmakers, only Lubitsch is Hitchcock’s equal in engaging with the audience, making us complicit in what’s going, trusting us to be co-creators of aspects of the story being told and teasing, tricking, playing with us in order to please and delight.

Stars:

The performances of the stars of Torn Curtain have been widely criticised, Thomson calling them ‘drab’ (p.402). Others regurgitating stories of how Hitchcock had wanted Eva Maria Saint and Cary Grant; how Paul Newman and Julie Andrews, the top box-office stars of this period, were imposed on Hitchcock by the studio; how Newman was — to Hitchock’s annoyance — too method; how he found Julie Andrews not beautiful or sexy enough.

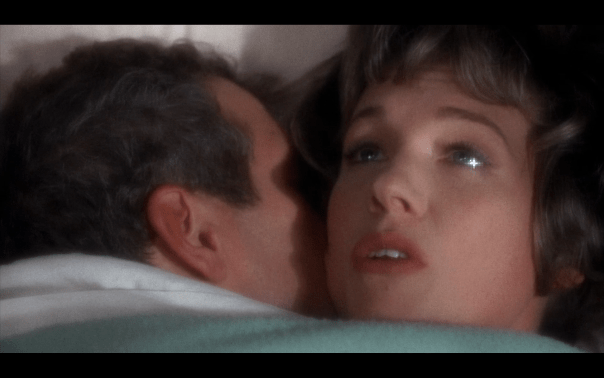

Be that as it may, there’s no question that he took great care with the presentation of these stars. We’re introduced to them in bed, with their coats over the blankets, making love and trying to keep warm. Then, we see their name tags of the characters they play in alternating close-ups, first Dr. Sarah Sherman and then Professor Michael Armstrong. We first see the backs of their heads, then extreme close-ups of the couple kissing. We know they’ve just had sex: ‘let’s call this lunch,’ says Armstrong. It’s a sexy spin on Julie Andrews’ star persona. Here is Mary Poppins and the novice from The Sound of Music in bed with Paul Newman; and they’re not even married! That must have been a thrilling star entrance to fans of both stars. Moreover, Hitchcock and his team light them beautifully. Look at the shine of the pin spot in Andrew’s eyes in fig. A. How Newman’s eyes, then widely publicised as the most beautiful blues in the world, are presented in an enormous close-up, so big as to encompass only one eye, made to shine against the light (fig. B). Note too, the prominent display of Newman’s body throughout the film (fig. C).

‘Performance’ is not everything in commercial filmmaking, particularly when it’s a question of stars. Newman and Andrews are not bad; the director makes an interesting play on audience expectations, giving them a theatrical star entrance, lighting them gorgeously, dressing them both attractively and meaningfully, and playing on and developing their star personas, particularly that of Andrews. I loved seeing them in this, and stars by their very nature should not need to play a ‘role of a lifetime’ to bring their audience pleasure; often their presence is enough for their fans. When presented as carefully and to so much advantage as here, it is much more than enough. Newman and Andrews were a draw then and are still reasons to see this film.

Performance:

It is true that the stars, delightful as they are to see, do not give memorable performances. But I do think it would be fair to say that some of the performances in Torn Curtain have become legendary. Wolfgang Kieling as Hermann Gromek, Armstrong’s East German body-guard, with his East-European accent and his American slang, funny and menacing, always watchable, is an outsize cartoon. It’s a particular type of performance, very theatrical, very knowing, aimed at the audience, and clearly a type Hitchcock delights in.

I’ve made a gif of his famous death scene so as to exaggerate his hand gestures (see above). This is an actor who knows how to make the most of a scene even in the absence of his face or even most of his body, who steals the scene from his co-stars by showing us his expiration only with a wave of his fingers, but they wave and wave, each movement expressing something slightly different but within an overall arc, like those hams who can turn being shot into a five minute dance with death. I find it delightful, so much better than merely ‘realistic’ and Hitchcock must have also, or he would have shot it differently, shortened it or cut it altogether.

Much as I love Kieling’s performance, one never gets a sense that he’s playing a real person. This is not true of Lila Kedrova’s marvellous turn as the Countess Kuchinska, the Polish Countess, not ‘communistical’, sneering at the quality of the tobacco and the coffee and desperate for American sponsorship of her visa application. As you can see below, each of her ‘faces’ is beautifully expressive, and she does run the gamut of expression.

I tried to do some image capture to illustrate and the enormous range of vivid expressions she brought even within one shot quickly became evident. No single still would do, so I created a compilation from her scenes in the cafe with Julie Andrews and Paul Newman. Kedrova’s performance is theatrical, almost Delsartean in her gestures, and she looks like a wounded French bulldog, but one gets a sense of a person who’s elegant, pained, powerful but helpless, bewildered. There’s a person that’s constructed out of those arresting expression and those wounded eyes. How did the countess arrive from Poland to East Berlin? What did she have to live through? It’s clear that she was once beautiful and that maybe she could no longer use that to the advantage she once did. What did her class, her gender, her beauty and her foreignness play in her survival? What sort of desperation drives an already old person to go to such lengths to get out?

I love the last shot in the clip above. The countess has finally gotten the American couple the information they needed. But just as they succeed the police arrives. She trips the policeman to allow the couple to escape, knowing that doing so seals her own doom. Hitchcock shows us a close-up of the rifle falling down the stairs, and then the camera cranes right up the stairs into a close-up of Lila Kedrova’s face as the Countess says, ‘My sponsor, my sponsor for United States of America’. It’s simultaneously camp and touching. Kedrova is giving a charismatic, theatrical performance (her elegant posture on the stairs, her voicing of the dialogue) that moves us through the recognisable humanity she expresses. For her all is lost. And Hitchcock wants us to see this enough to arrange a complex shot that is in itself arresting, spectacular. The American couple has a chance; for the Polish Countess in East Berlin, there’s no more hope. And Hitchcock and Kedrova, together, know how to convey the drama and truth of that moment, a moment where spectacle and feeling are rendered one. It’s lovely.

Dress, Décor, Angle and Framing as Part of Mise-en-scéne:

I understand that Hitchcock was disappointed with Torn Curtain but was pleased with what he’d been able to accomplish as an exercise on light and composition. These are some aspects of the film that aroused my interest and delighted my sight.

Poetry:

The reason why I started off writing this piece, but which I’ve left to the end, is that even in the worst of Hitchcock one finds moments of real poetry. In the scene below there are many things to admire. I decided to start the clip in the previous scene, so that you can see the close-up on Julie Andrews’ face as she says ‘East Berlin, but that’s behind the Iron Curtain’. That will rhyme with the very last shot of the scene, which is a masterpiece of expression. In between note how the cut is on Michael’s face seen slightly from behind now on the plane. From her to him, each facing in the opposite direction, and now in a new context, note how the camera tracks slowly back to allow us to take the new context in, and in full, before the camera pans right to a close-up of the befuddled Sarah. Note how the cutting speeds up when he sees her, the repetition of the tracking shot, but much faster as Michael heads to Sarah, then the change in direction but at the same speed as he approaches her. They’re superb choices.

But the pièce-de-resistance is the last shot on Sarah. That last close-up, after Michael has told her to stop following him and go home, which rhymes with the close-up of her finding out he’s going to East Berlin, but now filmed from a slightly higher angle to indicate Michael’s point-of-view on Sarah, and then the beautiful way the image begins to dissolve, goes out of focus, undulates, distorts. Note Hitchcock’s confidence in the length of its duration. And then the quick cut onto the opening doors of the plane with its view of East Berlin’s airport. It’s like all Sarah’s hopes, dreams, are extinguished and expire in that moment where everything goes out of focus and distorts only to be confronted by the harshness of a new reality with all her past knowledge put into doubt. It’s beautiful. A great moment of cinema. And one of many reasons to see the film.

I saw this on a gorgeous blu-ray transfer from Universal Studios: Alfred Hitchcock: The Masterpiece Collection.

José Arroyo

Torn Curtain has its charms – Kedrova and bits and bbs here and there. A minor film to while away the hours between life and death.