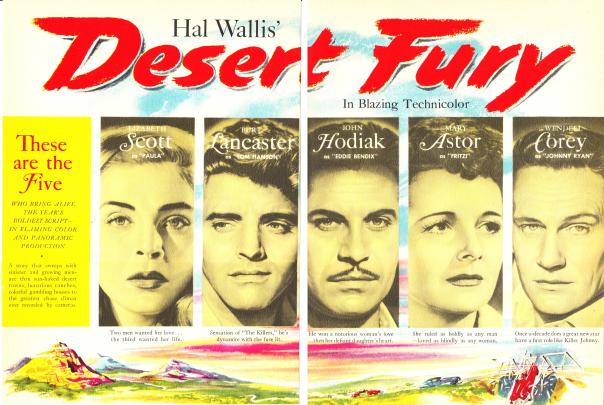

Burt Lancaster got his contract with Hal B. Wallis at Paramount on the basis of a test directed by Byron Haskin with Wendell Corey and Lizabeth Scott for Desert Fury. Lucky for him, the film was not ready to shoot for another six months and he was able to fit in Robert Siodmak’s The Killers(1946) for producer Mark Hallinger at Universal beforehand. Desert Fury started shooting two weeks before the release of The Killers but there were already whisperings of Lancaster as a big new star, and the whisperings were so loud that Hallinger gave him first billing and a big publicity build-up rather than the little ‘and introducing….’ title at the end of the credits that was then typical, and is indeed the billing offered Wendell Corey in Desert Fury as you can see in the poster above. Before Desert Fury started shooting, Hal Wallis knew he had a big fat star on his hands and that his part had to be beefed up so as to capitalise on it.

By the time the film was released on September 24th, 1947,, Burt Lancaster was the biggest star in the film. The Killers hit screens on the 29th of August 1946. As Kate Buford writes, Ít was an extraordinary debut for a complete unknown. Overnight he was a star with a meteoric rise ¨faster than Gable´s, Garbo´s or Lana Turner,¨as Cosmopolitan said years later (Buford, loc 1260). In New York the movie, ‘played twenty-four hours a day at the Winter Garden theatre, ‘where over 120,000 picture-goers filled the 1,300 seat theatre in the first two weeks, figures Variety called “unbelievably sensational.”‘ Brute Force was the fourth film Lancaster made, after I Walk Alone, but it was the second to be released, on June 30th 1947. According to Kate Buford, it too ‘set set first-week records at movie houses across the country’ (loc 1412).

Lancaster’s status as a star is reflected in the lobby card and poster above, where in spite of being billed third, what´s being sold is what Burt Lancaster already represented, the publicity materials giving a false impression that he is much more central to the narrative than is in fact the case. His image dominates in both, and even the tag lines are attributed to him: ‘I got a memory for faces…killer´s faces…Get away from my girl…and get going’, is the tagline in the lobby card. The text on the poster reads, ´Two men wanted her love…the third wanted her life.

In the ad below, he´s billed second, as ´the sensation of The Killers, Dynamite with the fuse lit’

When trying to recapture a past moment in relation to cinema, it´s often useful to look at trailers and other paratextual publicity materials. Trailers hold and try to disseminate the film´s promise to viewers. Of course, its purpose is to sell, to dramatise its attractions so that viewers will go see it. And of course, they often lie, dramatising not what is but what they hope will sell. That said, those promises, lies and hopes are often very revealing.

As you can see above, the trailer is selling melodrama — violent passions — in a magnificent natural setting filmed in Technicolor. Burt Lancaster’s name is only mentioned 39 second into the 1.41 trailer, after Lizabeth Scott with her strangeness and her defiance of convention and after John Hodiak with his secrets and coiled snakeyness. And Lancaster’s introduced as ‘hammer fisted’ Tom Hanson, erroneously giving the impression that this will be an action film. But note too that by the end of the trailer, Lancaster is given top billing.

According to Kate Buford, in Burt Lancaster: An American Life, Lancaster thought ‘Desert Fury would not have lunched anybody’, later ‘dismissing it as having ‘starred a station wagon’ (loc 1157). The film is really a series of triangles: Eddie (John Hodiak) and Tom (Burt Lancaster) are both in love with Paula (Lizabeth Scott), Fritzy (Mary Astor) has already had an affair with Tom who is currently pursuing an affair with her daughter Paula, Paula and Johnny (Wendell Corey) are both in love with Eddie etc. I have made a not-quite-video essay that nonetheless well illustrates the Johnny-Eddie-Paula triangle, surely one of the queerest of the classic period, which can be seen here:

Tom is really a fifth wheel in the narrative. But by the time the film started shooting, Burt Lancaster was already the biggest star in it. His part was beefed up to take his new status into account, scenes were added, According to Gary Fishgall, the film was based on a 1945 novel, Desert Town by Ramona Stewart, and ‘ Lancaster’s role was an amalgam of two of the novel’s characters: the embittered, sadistic deputy sheriff, Tom Hansen, and a likeable highway patrolman named Luke Sheridan. Neither character was romantically linked to Paula (p.55). But in the film, he ends up with Lizabeth Scott at the end. All these additions probably contributed to the film seeming so structurally disjointed.

In Desert Fury Tom, a former rodeo rider, just hangs around waiting for Paula to get wise to Eddie, leaving her enough rope to act freely, as he does with colts when taming them, but not enough so that she hangs herself, or so he thinks. Really, he’s extraneous. He gets to walk into the sunset with Paula at the end of the film but the film really ends once Paula and Fritzy kiss, on the lips. He certainly doesn’t get much to do during it, except for a couple of great scenes where Fritzy tries to buy him into marrying her daughter (above) and another bit of banter when she thinks he’s come to accept her offer (below). Mary Astor steals both scenes. In fact she steals everything. Every time she appears, her wit, weariness, intelligence, the intensity of her love for her daughter — she lifts the film to a level it probably doesn’t deserve to be in. But Lancaster is good. These are the only scenes in the film where he looks like he’s enjoying himself.

Tom is the closest the film has to a ´normal character’. Indeed, aside from the character he plays in All My Sons (1948) this is the closest Lancaster had come to such a type during the whole of his period in film noir in the late 40s and which includes all of his films up to The Flame and the Arrow in 1950. Even in Variety Girl, which is an all-star comedy where he and Lizabeth Scott spoof the hardboiled characters they’re associated with, the surprise is that they’ve already created personas to spoof in such a short time (see below).

According to Fishgall, ‘Lancaster –billed third before the film’s title — acquitted himself well in the essentially thankless other man’ role. Still, if Desert Fury had marked his screen debut as originally planned, it is unlikely that he would have achieved stardom quite so quickly. Not only did the film lack the stylish impact of The Killers, but so did the actor. Without the smouldering intensity of the Swede and his first pictures’ moody black and white photography, he appeared to be more of a regular fellow, and guy-next-door types rarely become overnight sensations’ (p. 67).

In Desert Fury we’re told that unlike the drugstore cowboys who are now criticising him, Tom used to be the best rodeo rider there was but a while back, whilst wrestling a steer, he got thrown off and is now all busted up inside. Being ‘busted up inside’ is what all the characters Burt Lancaster plays in the late ’40s have in common. He thinks of returning to the rodeo all the time but knows he can never be as good. He used to be a champ, now all he can hope for is to be second best. He knows he ‘ain’t got what it takes anymore’. He’s in love with Paula and she knows it. But she doesn’t know what she wants. He think he does: ‘you’re looking for what I used to get when I rode in the rodeo. The kick of having people say “that’s a mighty special person” I’d like to get that kick again. Maybe I can get it with just one person saying it’. He will, but he’ll have to wait until the end of the movie.

But even in this, Lancaster doesn´t play entirely nicey-poo, true-blue, throughout, and his Tom is given moments of wanton bullying and cruelty where he gets to abuse Eddie just because he’s a cop and wants to. And it´s interesting that it´s that moment, which jives so well with the ´brute force´Lancaster was already known for, and which would attach itself to his persona for many a year, that is the one chosen for the trailer.

According to Robyn Karney, in Burt Lancaster: A Singular Man, ‘As the straightforward moral law officer in a small Arizona town who rescues the object of his affections from the dangerous clutches of a murderous professional gambler, Burt had little to do other than look strong, handsome and reliable. Despite Wallis’ much vaunted rewrites, the role of the Sheriff Tom Hanson remained stubbornly secondary and uninteresting, with the limelight focused on John Hodiak as the villain, fellow contract players Elizabeth Scott and Wendell Corey’ (p.31).

I mainly agree with Robyn Karney except for four points, two textual and stated above: the first is that even in this Lancaster is playing a failure, someone once a somebody that people talked about but now all busted up inside; the second is that that element of being ´busted up inside´leads to a longing that gets displaced onto Paula. If the rodeo is what made feel alive and gave him a reason to live before his accident, now it´s Paula, and the idea that she might also be an unobtainable goal leads to his outbursts of unprovoked violence towards the rival for his affections, Eddie (John Hodiak).

The other two points of interest are extra textual. Desert Fury is gloriously filmed by Charles Lang. A few years later, in Rope of Fury, Lang would film Lancaster as a beauty queen: eyelashes, shadows and smoke, lips and hair (see below):

Here, even with his pre-stardom teeth and his bird´s nest of a hairdo, Lancaster sets the prototype for the Malboro Man:

He looks good in technicolour, and Lang brings out the blue of his eyes:

More importantly, the film visualises him, for the first time, as Western Hero, a genre that would become a mainstay of his career from Vengeance Valley (1951) right through Ulzana´s Raid (1972) and even onto Cattle Annie and Little Britches (1981):

Desert Fury was not well reviewed. According to the Daily Herald ‘The acting is first-class. But except for Mr. Lancaster as a speed cop, the characters in the Arizona town with their lavish clothes and luxury roadsters, are contemptible to the point of being more than slightly nauseating’ (cited in Hunter p. 27),

The Monthly Film Bulletin labelled the film a western melodrama, claiming, surprisingly, that ‘The vivid technicolor and grand stretches of burning Arizona desert give a certain air of reality to the film’. Hard for us to see this thrillingly melodramatic film, lurid, in every aspect, evaluated in the light of realism. The MFB continued with, ´This reality is however counteracted by the way in which the sharply defined, but extremely unnatural characters act. Everything is over dramatised, and the title is a mystery in that the desert is comparatively peaceful compared with the way the human beings behaved…Lizabeth Scott is suitably beautiful as Paula and Burt Lancaster suitably tough as Tom. (Jan 1, 1947, p. 139)

Thus, we can see that on the evidence above, the film was badly reviewed, Time magazine going so far as to call it, ‘impossible to take with a straight face’ (Buford, loc1293). But Burt Lancaster´s performance was either exempted from the criticism or its faults where attributed to the film rather than to himself. More importantly still, the film was a hit, Burt Lancaster´s third in a row. Finally, as I´ve discussed elsewhere, the film is now considered by many a kind of camp classic, a leading example of noir in technicolor as well as arguably the gayest film ever produced in the classic period.

José Arroyo

I finished reading the book wishing Jones had delved more deeply into the films themselves. For example, of my own favourite, The Set-Up, Jones tells us that according to his wife, Ryan ‘takes more pride in that movie than any other he ever made’. We’re shown how the film was based on a narrative poem that became a New York Times best-seller in 1928 and that Ryan had first read it in college; how the original protagonist was changed from black to white for the movies; how, like Hitchcock’s Rope, the duration of the narrative is the film’s running time, how the film influenced most other boxing films including Scorsese’s Raging Bull; how the film made Ryan a beefcake favourite with the bobby-soxers, and how after he saw it Cary Grant told Ryan, ‘My name’s Cary Grant. I want you to know that I just saw The Set-Up and I thought your performance was one of the best I’ve ever seen’. Re-reading the section on The Set-up I realised that it’s very good on the film’s production, its style, its reception and conclude that if he’d devoted as much time to each film, the book would be impossibly long.

I finished reading the book wishing Jones had delved more deeply into the films themselves. For example, of my own favourite, The Set-Up, Jones tells us that according to his wife, Ryan ‘takes more pride in that movie than any other he ever made’. We’re shown how the film was based on a narrative poem that became a New York Times best-seller in 1928 and that Ryan had first read it in college; how the original protagonist was changed from black to white for the movies; how, like Hitchcock’s Rope, the duration of the narrative is the film’s running time, how the film influenced most other boxing films including Scorsese’s Raging Bull; how the film made Ryan a beefcake favourite with the bobby-soxers, and how after he saw it Cary Grant told Ryan, ‘My name’s Cary Grant. I want you to know that I just saw The Set-Up and I thought your performance was one of the best I’ve ever seen’. Re-reading the section on The Set-up I realised that it’s very good on the film’s production, its style, its reception and conclude that if he’d devoted as much time to each film, the book would be impossibly long.