The first time I saw La Terra Trama was about thirty years ago and I was at least as deeply moved seeing it again yesterday. I found myself consulting Geoffrey Nowell-Smith’s indispensible Visconti (London: BFI, 1967, 1973) to find out more but there were so many interesting facts to take into account – for example, a small amount of capital for the film was advanced by the Communist Party for what was originally meant to be a short; then it evolved into a three-part epic on the liberation struggles of fishermen, peasants and miners before finding its current form – and I found myself wanting to argue to such an extent with Nowell-Smith’s interpretation of some incidents, that my writing risked bypassing the film in favour of Nowell-Smith’s take on the film. I concluded that I had better put Nowell-Smith aside for now and just focus on writing down my impressions, what I felt and thought upon seeing the film again, and why and how it had moved me so.

I find La Terra Trema to be one of the treasures of Twentieth Century Art and the work of a poet with a generous heart, an incisive mind and the skills of a virtuoso (as a an aside, but perhaps worth noting, Francesco Rosi and Franco Zefferelli, as opposite as directors can be, both worked as assistant directors with Visconti). The film begins by showing us a way of life that has persisted for centuries: men going out to fish, women cleaning up the house as they await the men’s arrival, a return that is not always certain; young people desiring love and a better way of life whilst clearly knowledgeable and observant of the limits placed on these desires by the changing wealth and social position of their families and focussing on what they think is important: home, family, society. These houses and how people use them evoke a way of life – places, people, relationships to places and relationships amongst different peoples — as well as a structure of feeling – a felt way of understanding these changing relationships — which to my mind no Hollywood film has even come close to.

The Valestro family is composed of one set of grandparents, a mother and seven children who all live under the same roof. The father has already died at sea but everyone else, no matter what their age, contributes to the family’s subsistence and survival. I found the depiction of the houses, the clothes, the furnishings, the rituals, recognisable; and I daresay this would be the case for many a Southern European born even into the last half of the last century (and certainly by their parents). The film’s on-location shooting and non-professional actors add an awkwardness that is also a series of grace-notes to what we see. It feels a document even as we are at all times aware of the way the drama is being shaped for us, acted out, narrated. The film, which in some ways seems to fall within a particular tradition of documentary, perhaps Grierson’s ‘creative shaping of actuality’, is ostensibly loosely based on Giovanni Verga’s novel I Malaboglia (1881)/The House by the Medlar Tree.

I was moved also by the grandfather’s sayings — ‘Strength of youth, wisdom of age’, Every wind is a bad wind for a sinking ship’ — which reminded me of the sayings my grandmother uttered as she slapped her hands on her knees to end a conversation: rhymes appropriate to the occasion that encapsulated the wisdom passed down to the family through the ages from and to people who could neither read nor write.

The film offers a complex account of the duties and obligations involved in being a member of the family and the oppressions and pleasures, the aid, ease, (as well as limitations) of being part of the village and the community, which is why it’s loss will be so felt. It begins with women, getting up and getting the house ready for the men of the house who have been out fishing all night, the money being shared equally except for the youngest, who must be no older than seven, and gets half. All of the first part is devoted to showing us this way of life in all its complexities, with its clear-cut economic exploitation but also with many variegated pleasures in spite of being a subsistence economy. All of this will be lost when the eldest son, Antonio, decides to fight for a better and more just way of life.

After a spontaneous revolt against the injustice of the wholesalers at the port in which Antonio, the eldest son, gets jailed only to be arbitrarily released, the family together vote to try for a new way of life, to mortgage the home that has been in the family since time immemorial to try to bypass the wholesalers and get a better deal for their fish. Initially, they strike it lucky with a shoal of anchovies, though even here good fortune extolls a price, as some of the siblings – such as Mara, the eldest, are now too rich to marry those they’d set their heart on when poorer: The film, whilst giving a complex and variegated of love and desire, is completely unsentimental about money and marriage. But then, the need to pay bills, force them onto recklessly fishing in bad weather. They’re lucky to return with their lives but their boat is lost, and with it the ability to earn an independent living. And things get worse, as the wholesalers now refuse them day work

From this point, the film turns into tragedy. As the narrative tells us each branch of the family withers and falls: Antonio is so depressed, he sleeps and drinks, Cola, the second oldest brother leaves home for the sea and the film hints also at a life of crime, the grandfather’s in hospital, the eldest sister now has her marriage hopes dashed because she’s too poor instead of too rich, and the second eldest sister first shown to us looking in a mirror and arranging her hair has now fallen into accepting cheap gifts from men in a way that is whispered about and makes her un-marriageable. ‘Your pride has made you the worst family in Trezzo’ Antonio is told. But that is not the end of their suffering. Antonio, who had thought himself so poor he dreamt of food before, is now forced to sell the good and practical clothes he has left in order to get food, and finally has to suffer complete humiliation in front of his whole community and dressed in tatters before being given a job again and returned to much less than his wealth and position was at the beginning of the film.

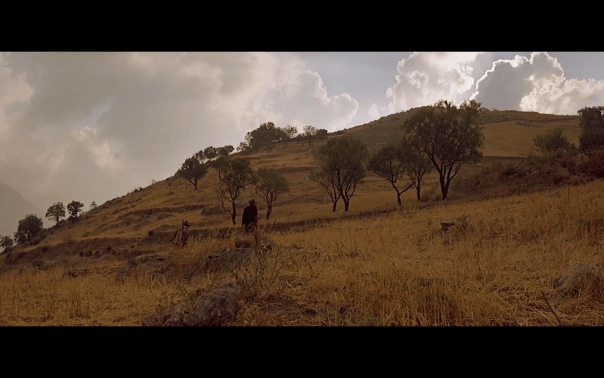

Visconti shows us all of this in very beautiful and complex long shots and long takes with a whole view of life expressed in the background. The frame is always full except for select moments, those striking simple images of the women on the rocks waiting for their men, or the moment where Lucia cries and clutches at the bracelet she too quickly accepted. Visconti usually lets your eye wonder but these people are always individuals in a community. They are rarely alone; that is their strength and that is also what ails them. The Valestros could be the family that will emigrate to Milan in Rocco and His Brothers.

What I found a weakness thirty years ago, the voice-over narration, I now find a strength for it’s not a Voice-of-God, this-is-the-way-you-must-think narration. It’s explicatory, parenthetical, indicative, and it renders poetic that which it dramatises. I find it beautiful. I also love the way Visconti lets the viewer’s eye wonder along the frame; there’s a focus on a particular character and action, but all other kinds of things are going on in the background — the setting is always social, people are usually interacting, working; these people are always individuals in a community. The only times we are shown individuals filling a frame are poetic moments of interiority but usually the result of and a comment on the communal, social, contextual. I love that Visconti makes these people beautiful, dignified. Their feet might be bare and their clothes ragged but their hearts are full and their faces and bodies as beautiful as those of any.

There are a few things that strike a discordant note. The way the rich baroness is shown toothless and eating, the melodramatic and overdone attacks on the wholesalers by linking them to Mussolini and fascism… But to me these are rendered very minor in the face of the film’s accomplishments. That La Terra Trema shows these beautiful and dignified people revolting is so moving, their conditions of existence so bare, the depths they could yet fall to, so great. The impossibility of fighting against these conditions individually is made so clear. Yet, there is hope in the struggle, in the same community that oppresses one, and someone might yet be fixing the boat you sunk in your struggle and ask you to come and visit it one day.

I wish someone had made such a film about my people. Others can quibble, though there is very little indeed to quibble with, but only Visconti made such a film, and only in Italy. Thus it has to stand for all the other Southern European, or Mediterranean conditions and ways of life, not so dissimilar from that depicted, as a record, a warning, and as we hear reports of slavery amongst fishermen in the South Seas, as a reminder of such exploitation that the very earth trembles in indignation. It’s a truly great film.

José Arroyo

Like this:

Like Loading...